The evolutionary path of domestic cats has led them to become obligate carnivores, a dietary specialization that comes with a critical biological trade-off: their inability to synthesize taurine, an essential amino acid. Unlike many other mammals, cats lack the enzymes required to produce taurine from precursor molecules, forcing them to rely entirely on animal-based sources for survival. This nutritional defect is not a random flaw but rather a consequence of their genetic adaptation to a meat-exclusive diet—a "lock" that ensured efficiency at the cost of metabolic flexibility.

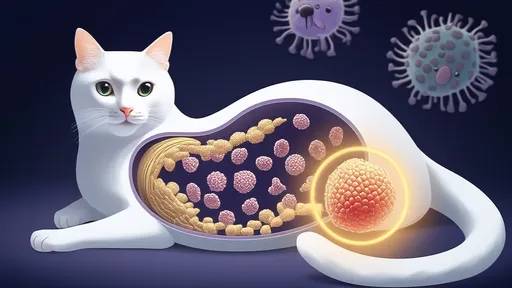

Taurine deficiency in cats isn’t merely a dietary inconvenience; it’s a life-threatening vulnerability. Without adequate intake, cats develop severe health issues, including retinal degeneration leading to blindness, dilated cardiomyopathy (a fatal heart condition), and reproductive failures. The irony is that while modern cats are often perceived as independent hunters, their biology makes them perpetually dependent on prey—or commercially fortified food—to avoid systemic collapse. Wild felines obtain taurine from organ meats like liver and heart, but domestic cats fed unbalanced diets (e.g., vegetarian or cooked meat without supplements) face rapid decline.

Scientists trace this metabolic constraint to a mutation in the CSAD (cysteine sulfinic acid decarboxylase) gene, which effectively disabled taurine synthesis in ancestral cat species. What’s fascinating is that this genetic "lock" likely persisted because it conferred no disadvantage in environments where prey was abundant. Natural selection favored energy-efficient traits: Why waste resources synthesizing taurine when it could be readily scavenged from prey? Over millennia, the gene became nonfunctional, cementing cats’ status as strict carnivores.

The discovery of taurine’s role in feline health revolutionized pet nutrition. In the 1980s, researchers linked commercial cat food formulations lacking taurine to widespread heart disease in household pets. This led to mandatory supplementation in all reputable cat foods today. Yet, the broader implication remains underappreciated: Cats are a striking example of how extreme dietary specialization can render a species hostage to its own adaptations. Even small deviations from their evolutionary diet trigger catastrophic consequences—a lesson for understanding nutritional needs in other specialized carnivores.

Beyond practical pet care, the taurine dependency highlights a paradox in feline evolution. Cats are both apex predators and nutritional prisoners. Their sleek hunting prowess masks a fragility rooted in their genes. While dogs, with their omnivorous flexibility, thrived on human scraps throughout history, cats’ survival hinged on consistent access to whole prey. This dichotomy explains why feral cat colonies often struggle in resource-scarce environments unless they hunt rodents or birds daily. Urban strays fed exclusively on carbohydrate-rich garbage suffer disproportionately from taurine-deficiency syndromes.

Modern bioengineering has yet to "fix" this genetic defect, partly because doing so might unravel other optimized traits in feline metabolism. For now, the solution remains elegantly simple: Feed cats like the carnivores they are. Whether through premium commercial diets or carefully balanced raw meals, taurine supplementation isn’t optional—it’s the price of sharing our homes with a creature whose genes refuse to compromise on meat.

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025